Review: 'Green Fairy', by Kyell Gold

Solomon Wrightson, a wolf senior at Midland’s Richfield High, is in trouble. During his childhood and early adolescence, he was a bit of a loner but basically just one of the kids with his classmates. In high school, the wolves have tended to be the jock gang, going out together on the school baseball team. The coyotes also hang together, although they are looked on as second-class wolves.

Solomon Wrightson, a wolf senior at Midland’s Richfield High, is in trouble. During his childhood and early adolescence, he was a bit of a loner but basically just one of the kids with his classmates. In high school, the wolves have tended to be the jock gang, going out together on the school baseball team. The coyotes also hang together, although they are looked on as second-class wolves.

But in their senior year, it all starts to fall apart for Sol. He had realized the year before that he is gay, and had joined a gay e-mail group where he formed a relationship with Carcy, an older ram living four hours away in Millenport. Sol thought that he had kept this a secret except from his study partner who is also his only friend, Meg Kinnick, a sardonic otter goth girl; they are two loners hanging out together. They have planned to go to Millenport together the next summer when Sol gets a car; Meg to get a job away from her parents, and Sol to move in with Carcy.

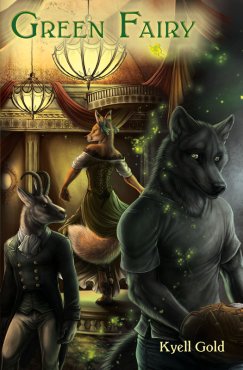

Sofawolf Press, March 2012, trade paperback $19.95 (vii + 263 pages). Illustrated by Rukis.

However, the emotional pressure of keeping his emerging homosexuality a secret is wearing Sol down:

Part of it was that for the last year, Sol had been terrified that he would let something slip about being gay. It had started out innocently enough, a couple weeks over the summer reading some material online, the burst of realization, the growing wave of guilt afterwards. He’d created an anonymous e-mail account to post to a forum for gay teens, where Carcy’d been one of the people to tell him there was nothing wrong with him. E-mail had led to IM had led to texting, and Sol had gotten his head around his sexuality without having to talk to anyone in his family, or at his church. Or the team. (pgs. 47-48)

Also, although Sol had not cared much, his lack of interest in girls has been noticed by his classmates who suspect he may be gay. His loss of interest in baseball, coming just when Taric, a coyote senior is trying particularly hard to make the team, leads Mr. Zerling, the wolf coach, to take Sol off the starting spot as the team’s second baseman and give it to Taric. This in turn leads Sol’s jock father to threaten to withhold the car unless Sol gets back onto the team:

Also, although Sol had not cared much, his lack of interest in girls has been noticed by his classmates who suspect he may be gay. His loss of interest in baseball, coming just when Taric, a coyote senior is trying particularly hard to make the team, leads Mr. Zerling, the wolf coach, to take Sol off the starting spot as the team’s second baseman and give it to Taric. This in turn leads Sol’s jock father to threaten to withhold the car unless Sol gets back onto the team:

‘Listen,’ his father said. “There’s no reason you shouldn’t be better than a coyote at baseball. They might be a little faster, sure, but baseball’s a team sport and you’re part of a pack. No reason you shouldn’t be better.

Sol squirmed in his seat. It wasn’t fair. He’d made it through eleven and three-quarters years of school doing well enough to play. Why couldn’t coach have waited just two months before demoting him? Even if it had happened after his birthday, he’d have the car. He could run away to Millenport with Meg as soon as he graduated. Just having that to look forward to would make the tension in these evenings tolerable. He tried to think back to when he’d been able to have a relaxing time with his father, and the last time he could remember had been when they’d gone to Natty’s [his older brother] last football game. (p. 47)

But this is only half of the complex plot of Green Fairy. As part of a school project with his study partner, Sol has to read a 1901 book, a translation of The Confession of Jean de Giverne, written by the teenage de Giverne from his prison cell while awaiting execution for the murder of his gay lover. Sol’s reading of this, while under the influence of Meg’s green absinthe, causes him to vividly “go into” the lives of the spoiled Gallian chamois dandy and his lover, a transvestite dancer in the chorus line at the infamous Moulin Rouge, the most scandalous establishment of Lutèce’s notorious Montmartre district:

To an innocent chamois, as I was just two months ago, the chaos and cacophony of Montmartre is bewitching. It is an explosion of bright colors, a flood of smells, a patchwork of language from all corners of Gallia, gathered in a honeycomb of small rooms, each of which seems to have a window giving out onto the street and a fox, a badger, a rabbit, a mouse leaning out of it shouting or singing. It gives one the air of having entered a new world, and in early April, the ragamuffins sell dewy blooms of flowers just showing cracks of color through their green shells, the bohemians pull out their paintings of blue skies and vast gardens to show under the shelter of oilcloth with the light rain hissing softly atop. Father, father, can you see why I followed Thierry there? (p. 22)

In a series of alternating episodes, set off by a different typeface, Gold transports the reader along with Sol into the flamboyant life of Montmartre in 1901 and of Jean and the white-furred Niki. But as Sol’s RL life deteriorates – Taric and his older sister Tanny are bad winners who go out of their way to harass Sol; his father tries to imprison him in a hated summer job; his obsession with becoming a vegetarian (like Carcy), which makes his wolf father doubt his sanity, begins to undermine his health; he gets hints that Carcy’s love for him is barely superficial – and he uses more and more of Meg’s absinthe to go deeper and deeper into Jean’s world, Sol finds himself seguing from focusing upon Jean to focusing upon Niki in the first person (in a third typeface). He becomes an invisible observer of the transvestite fox’s home life in a garret shared with a suicidal rat artist, Henri Trounoir. And he gradually becomes aware that he is seeing things that Jean never saw; that could not have been in Jean’s manuscript.

In a series of alternating episodes, set off by a different typeface, Gold transports the reader along with Sol into the flamboyant life of Montmartre in 1901 and of Jean and the white-furred Niki. But as Sol’s RL life deteriorates – Taric and his older sister Tanny are bad winners who go out of their way to harass Sol; his father tries to imprison him in a hated summer job; his obsession with becoming a vegetarian (like Carcy), which makes his wolf father doubt his sanity, begins to undermine his health; he gets hints that Carcy’s love for him is barely superficial – and he uses more and more of Meg’s absinthe to go deeper and deeper into Jean’s world, Sol finds himself seguing from focusing upon Jean to focusing upon Niki in the first person (in a third typeface). He becomes an invisible observer of the transvestite fox’s home life in a garret shared with a suicidal rat artist, Henri Trounoir. And he gradually becomes aware that he is seeing things that Jean never saw; that could not have been in Jean’s manuscript.

Sol is concerned that he may be drinking too much absinthe; that his hallucinations are getting out of control. Then he starts waking up with physical souvenirs from Niki’s life …

This is Kyell Gold’s most ambitious work to date. It seamlessly interweaves and brings to life three lives, one from America’s present and two from the “Lutèce” of more than a century ago, as Sol desperately tries to learn whether the past is only a green-poison hallucination or if Niki and Henri really lived. It is filled with Gold’s signature worldbuilding; a convincing mixture of our world (references to the Moulin Rouge and Vincent van Gogh), and the anthropomorphic:

[Sol is visiting Meg at her parents’ otter house for a study session.]

Meg Kinnick lived in a smallish house with rounded walls and circular windows, like most of the houses along the lake. In the daylight hers stood out because of its bright yellow dome roof and lime green trim, which Sol had more than once heard called an “eyesore,” but at night, the green softened and the yellow turned a lovely silver. It was granite, older than Sol’s house, though they’d had the roof replaced just last year.“Hi, Mrs. Kinnick,” he said at their door, which had a huge daisy painted on it. “Meg and I have a project to work on.”

“C’mon in, Sol.” The skinny otter beamed up at him. Water glistened on her mostly-exposed fur and pooled around her feet as she stepped back carefully to let him in. He avoided the water and breathed in the floral, humid air of the large, open atrium. To his right, in an irregularly cut-out third of the room, was the opening to the communal pool where Meg’s father floated on his back, wearing nothing but a damp towel loosely draped across his midsection that floated in the water. Sol was sure it had only just been dropped there. “Hi, Mr. Kinnick,” he said.

Meg’s mother slid back gracefully into the water, so smoothly and quietly that Sol’s whiskers caught the motion while his ears heard nothing. Her husband raised a paw as she swam out to him. “Well met, Sol,” he said. “Universe treating you well, I hope?”

“Most of it.” Sol glanced upward at the paused movie projected onto the screen that hung below the roof’s metal framework. “How are you doing?” (p. 13)

[Jean and his friend Thierry are relaxing at a sidewalk café in Montmartre.]

[…] and watched the people roaming about the street. The dampness in the air soaked up their scents as they passed, so much sharper and more real than in our refined streets. There were few perfumes, only the unadorned, raw scents of food, of clothing, of foxes and goats and rats and rabbits. It took me very nearly an hour to be at my ease, with my own perfume and fancy clothes.I was dressed in my fine silks, with a camel-hair coat to keep off the rain, and the cravat you gave me for my birthday wrapped gaily about my neck. Thierry was dressed more soberly, though he did leave his shirt open around his impressive chest. Even with the grey fur about his cheeks and the droop of his antler-less head, I was surprised to hear the shop owner refer to him as my father. Even a rat, after all, should know that the child of a red elk would in no way resemble a tan-furred, delicate chamois. Yet I suppose that to a rodent, all horned people are alike, much as I could be forgiven for mistaking a young mouse for the rat’s son, should I ever suffer such a lapse in perception. (pgs. 22-23)

[Niki returns home to his garret.]

Henri does not ask it either, when Niki returns home with a warm loaf of bread from the bakery down the street, fresh from the ovens. Dawn is still no more than an idea on the horizon, but Henri is awake, sketching in the silver moonlight. His painting is taking shape, a dark cloud of leaves overshadowing a female mouse reclining, her arm up to shield herself from the leaves. He describes the leaves with quick stabs of charcoal, but for the mouse he uses touches so delicate that Niki marvels that they leave traces on the canvas at all.Niki leaves the bread on the bed next to Henri. The black rat appears to take no notice of it, so absorbed is he in his painting. ‘It’s beautiful,’ Niki says, eating the bread he took for himself. The warm crust gives a satisfying crunch between his teeth; the warmer interior is soft and delicious.

‘Bah. The Dutchman could paint something twice as beautiful in half the time.’ (p. 89)

Sofawolf Press says that, “Green Fairy is Kyell Gold's first non-adult book. The novel contains characters that are involved in homosexual relationships, but there are no explicit depictions of sexual acts.”

Even so, Green Fairy is so steeped in gay homosexuality that the reader may not even notice that there are no explicit scenes. I have to say, ‘buy according to your tastes for this sort of thing’; but if you do not read Green Fairy, you will miss a piece of magnificent literature!

This superior book has superior illustrations. The wraparound cover and interior art by Rukis are practically worth the cover price by themselves.

Read more: Kyell Gold discusses Green Fairy with interviewer Isiah Jacobs

About the author

Fred Patten — read stories — contact (login required)a retired former librarian from North Hollywood, California, interested in general anthropomorphics

Comments

Well, I'm picking this one up, then.

I mean, I'm just not the audience for gay erotica, and hell, not really the biggest fan of romance, straight or gay, but at least I won't be missing the main point, as it were.

My mom loves historical romance, which this is kinda, though.

...

Probably still won't recommend it to her, however.

Wow, no sex scenes? I'll be sure to check this out for sure.

Post new comment