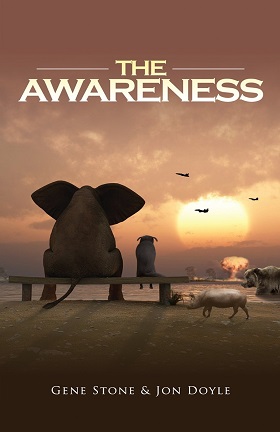

Review: 'The Awareness', by Gene Stone and Jon Doyle

"Every now and again I sit back and wonder what it would be like if other animals could really fight back against the egregious violence to which we subject them in a wide variety of venues ranging from research laboratories and classrooms to zoos, circuses, rodeos, factory farms, and in their own homes in ours and in the wild. This thought experiment takes life in The Awareness and reflects their points of view, and it's clear they do not like what routinely and thoughtlessly happens to themselves, their families and their friends. By changing the playing field Gene Stone and Jon Doyle force us to reflect how we wantonly and selfishly abuse other animals and the price we would pay if they could truly fight back. This challenging book also asks us to reflect on the well-supported fact that we need other animals as much as they need us. It should help us rewild our hearts, expand our compassion footprint, and stop the reprehensible treatment that we mindlessly dole out." - Marc Bekoff, Professor Emeritus of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Colorado (quoted blurb)

Suspense/terror/horror stories in which all animals, or all of certain species, turn against mankind go back at least to Arthur Machen’s unreadable “The Terror” (1917). Probably the best-known is Daphne du Maurier’s “The Birds” (1952). I recently reviewed Steven Hammond's Rise of the Penguins (2012). In movies, the terror-animals have ranged from rats to all of the giant mutations like Them and Night of the Lepus.

How successful any of these are usually depends on two factors. The skill of the author (or the director) in building a mood of terror, and the plausibility of the reason given for the animals to turn against humanity. In The Awareness, both of these fail.

NYC, The Stone Press, March 2014, paperback $14.95 (ix + 221 [+3] pages), Kindle free.

The impalas and the cheetahs lead their assault like an amber armada. Running swiftly, they tear into the tourists on safari and locals selling goat meat at the market. The impalas ram into the humans with their graceful, streaked heads. The cheetahs finish off the wounded.

A herd of bison from somewhere on a high plateau charges a small general store in the Dakotas.

Water buffalo gore Vietnamese day workers in the peaking heat of a low-country rice paddy. (p. ix)

All mammals gain intelligence – the Awareness - and turn against man. The novel follows four North American animals in particular, in alternating chapters of a dozen to fifteen pages each: a male brown bear in the Canadian Rocky Mountain forests; Nancy the elephant in a small traveling circus passing through rural northern Texas; Cooper the pet mongrel dog from New York City; and female Pig 323 on a North Carolina commercial farm. The bear, the elephant, the dog, the pig; then the dog, the bear, the pig, the elephant again; the pig, the elephant, the bear, the dog; and finally the elephant, the pig, the dog, and the bear.

These are among all of the other mammals in the world. The animals not only all gain human-level intelligence, they can speak English – or whatever the local human language is. A mountain hare thanks the bear for not eating him. Nancy the mature elephant speaks wisely with a naïve goat kid in the neighboring cage. Cooper the dog, who has been the human Jessie’s pet, argues with Jessie’s pet cat Clio and talks with Jessie. Pig 323 persuades the other pigs in her large but cruelly cramped pen to coordinate in a breakout.

The animals also all realize instinctually that they must revolt against humanity. Only Cooper wants to remain loyal to his human friend. All four animals have adventures. They meet other animals and humans in the war/revolution against human dominance. When Pig 323 finds the other pigs impractical, she and a ferret go off together. Nancy, Joe the kid, some monkeys, zebras and giraffes and other escaping circus animals meet a militant squad of local Texas animals; a peccary, a skunk, a jaguarundi, some possums, etc. Although all mammals turn against mankind, they do not agree among themselves how best to fight. The four become the leaders of their small groups.

You may like The Awareness. Unlike other animals-vs.-humanity stories, the protagonists are always the talking animals, not the humans. There are lots of well-written animal conversations, and a few animal-human ones:

"We’ll take our chances in the other direction," she [Nancy] said.

The peccary scoffed.

"There is nothing there but skinny coyotes, slow armadillos and desert field mice. They have nothing to offer. They are fighting in circles."

"Isn’t that all the more reason to join them?"

The antelope with the deformed antlers chimed in. "You don’t understand. They won’t have you join them. They want to do everything their own way. Even if that means losing." (p. 131)

But! There is never any mood of terror or suspense. Almost all the warfare is offstage. All of the four animal protagonists seem primarily philosophical. Some of the incidental animals are bloodthirsty, but the four focused upon spend most of their time wondering to themselves and the others of their group, “Why are we killing humans? Yes, the humans are often callous toward animals, and now that there is warfare between animals and humans, we have to protect ourselves. But in the greater scheme of life, why?”

I am more offended by the lack of any rationale for “the awareness”. All of a sudden, all mammals can talk with one another and with humans - the dogs and cats and raccoons and squirrels and coyotes and farm livestock and lions and tigers in the circuses and so on. Does anyone wonder about this commonality of language, with so many different mouths and vocal chords? No. If all animals are an equal brotherhood, what are the carnivores going to eat? The circus big carnivores conveniently get killed before anyone has to worry about that. Why do all mammals, including the up-to-now peaceful pets and the deer, prairie dogs and other wildlife who have never seen humans before, get the urge to charge into civilization and start killing all the humans? Why is Cooper an exception when other pet dogs attack their humans? No answer, ever.

I could not help thinking of two non-anthropomorphic science-fiction novels: Brain Wave by Poul Anderson (Ballantine Books, June 1954), and The Fittest by J.T. McIntosh (Doubleday, June 1955). In Brain Wave, all life on Earth becomes exponentially more intelligent. The animals gain human-level intelligence, but the humans become so intelligent that they leave Earth to the animals and migrate into the universe. (The novel focuses on the humans; the animals are offstage.) In The Fittest, a scientist’s experiment makes some cats, dogs, rats and a few other animals intelligent enough to revolt against human domination, but the novel ends with the intelligent animals (who do not gain speech) beginning to turn on each other. Compared to them, The Awareness seems poorly thought out and a disappointment.

About the author

Fred Patten — read stories — contact (login required)a retired former librarian from North Hollywood, California, interested in general anthropomorphics

"Every now and again I sit back and wonder what it would be like if other animals could really fight back against the egregious violence to which we subject them in a wide variety of venues ranging from research laboratories and classrooms to zoos, circuses, rodeos, factory farms, and in their own homes in ours and in the wild. This thought experiment takes life in The Awareness and reflects their points of view, and it's clear they do not like what routinely and thoughtlessly happens to themselves, their families and their friends. By changing the playing field Gene Stone and Jon Doyle force us to reflect how we wantonly and selfishly abuse other animals and the price we would pay if they could truly fight back. This challenging book also asks us to reflect on the well-supported fact that we need other animals as much as they need us. It should help us rewild our hearts, expand our compassion footprint, and stop the reprehensible treatment that we mindlessly dole out." - Marc Bekoff, Professor Emeritus of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Colorado (quoted blurb)

"Every now and again I sit back and wonder what it would be like if other animals could really fight back against the egregious violence to which we subject them in a wide variety of venues ranging from research laboratories and classrooms to zoos, circuses, rodeos, factory farms, and in their own homes in ours and in the wild. This thought experiment takes life in The Awareness and reflects their points of view, and it's clear they do not like what routinely and thoughtlessly happens to themselves, their families and their friends. By changing the playing field Gene Stone and Jon Doyle force us to reflect how we wantonly and selfishly abuse other animals and the price we would pay if they could truly fight back. This challenging book also asks us to reflect on the well-supported fact that we need other animals as much as they need us. It should help us rewild our hearts, expand our compassion footprint, and stop the reprehensible treatment that we mindlessly dole out." - Marc Bekoff, Professor Emeritus of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Colorado (quoted blurb)

Comments

I actually found "The Terror" to be about the only readable thing Machen ever wrote; I got sick of a certain poster on the old Portal of Evil forums badmouthing H.P. Lovecraft by pointing out that Machen did a lot of the same things first, which is true, and did it well, which is not true. But I did like it; death by swarm of moths is a lot scarier than you'd think. Funnily enough, Machen's book, though first, could also be considered a bit of a subversion of the usual "nature run amok" story; it ends with speculation that humanity has not been harsh enough on animals, and the animals, sensing weakness, have attacked.

Both versions of "The Birds" also don't explain what the heck is going on, but this is used by Maurier and Hitchcock to ratchet up the tension. However, in the trailer for the movie Mr. Hitchcock cheekily implies the question isn't "why are the birds attacking?" but "what took them so long?" (and, off topic, but Alfred Hitchcock trailers are awesome).

Them! definitely shows its age, but it's still worth watching, especially seeing as how the giant ants are kept off screen for quite a while. I still haven't gotten to see Night of the Lepus, but if I had to pick one movie I'd like to see remade, it's that one as a modern horror comedy. Oh, and speaking of famously bad movies, M. Night Shyamalan's The Happening shows why most people use animals for this kind of thing, and not plants.

Post new comment